By: Russ Kamp, CEO, Ryan ALM, Inc.

I recently stumbled onto an article that was highlighting the impending pension crisis (disaster) that is unfolding in Florida. The author’s primary reason for concern is the fact that there are now more beneficiaries collecting (659,333) than workers paying in (459,428). Briefly mentioned was the fact that the pension system currently has a funded ratio of 83.7% up from 82.4% last year. The fact that there are more recipients than those paying into the system is irrelevant. DB pension systems are not Ponzi Schemes, which in nothing more than a fraudulent vehicle that relies on a continuous influx of new “investors” (substitute plan participants) to pay the existing members of the pool.

A DB pension’s promises (benefit payments) are calculated by actuaries who have an incredibly challenging job of forecasting each individual’s career path (tenure), salary growth, longevity, etc. They do a great job, but they’ll be the first to tell you that they don’t get the individual participant calculations correct, but they do an amazing job of getting the total universe of payments nearly spot on. An acquaintance of mine, who happens to be an excellent actuary shared the following, “pension plans are funded over an active member’s career so that there will be sufficient funds to pay retirement benefits for life. The funding rules in Florida require contributions to get the plan 100% funded over time.”

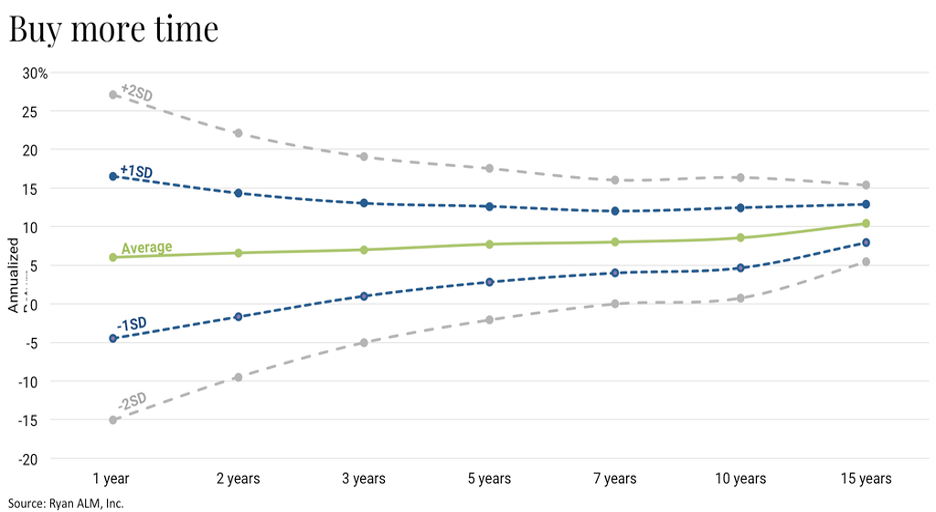

Granted, there are states that have not made the annual required contribution, in some cases for decades, and those plans are suffering (poorly funded) as a result. That isn’t the actuary’s issue, but they are left to try to make up the difference by forecasting the need for greater contributions and more significant returns. The payment of contributions comes with little uncertainty, while the reliance on greater investment performance comes with a huge amount of uncertainty over short time frames. I wouldn’t want my pension fund or livelihood (Executive Director, CIO, etc.) dependent on the capital markets.

I frequently hear the concern expressed about negative cash flow plans (i.e. contributions do not fully fund benefits). Why? If pension systems are truly designed based on each participant’s forecasted benefit, mature plans are bound to eventually fall into negative cash flow situations. These plans are designed to pay the last plan participant the last $1 of assets. These pension systems aren’t designed to be an inheritance for some small collection of beneficiaries who make it to the finish line. Importantly, there should be different investment strategies used for plans that are collecting more than they are paying out versus those in negative cash flow situation.

DB pensions are critically important retirement vehicles that need to be protected and preserved. Fabricating a crisis based on an incorrect observation is not helpful. If plan sponsors contribute the necessary amount each year and manage the assets prudently, these pension systems should be perpetual. Neglect the basics and all bets are off!