By: Russ Kamp, Managing Director, Ryan ALM, Inc.

One of the greatest attributes of managing a cash flow matching (CFM) portfolio is the fact that we don’t have to predict the direction of US interest rates. Most of us don’t have a clue about the direction, let alone the magnitude of the potential move. With CFM, you build the portfolio, and the cost reduction (savings) is locked in on day one, as future values are not interest rate sensitive.

Clearly, we and the plan sponsor community would like to see US rates remain fairly elevated, as higher rates equate to lower cost and more savings when using a CFM strategy. They also mean that coverage of the annual return on asset (ROA) objective is more certain, as opposed to traditional asset allocation frameworks that come with incredible volatility (annual standard deviation) and greater uncertainty in this environment.

All this said, we, at Ryan ALM, are still students of the markets, especially related to interest rates and the factors that impact those rates, such as GDP growth, labor markets, wages, inflation, geopolitical risk, etc. Clearly, the US investing community is excited at the prospect of the Fed’s FOMC cutting rates on September 18th. There appears little question that the Fed will act at that meeting. What is unknown at this time, is the magnitude of the potential cut. Will it be 25 bps or 50 bps or something entirely different. Who knows? However, those engaged in fixed income management certainly seem to have decided that rates will fall precipitously, as the Fed finally realizes the “error” of its way and reduces rates in a very meaningful way.

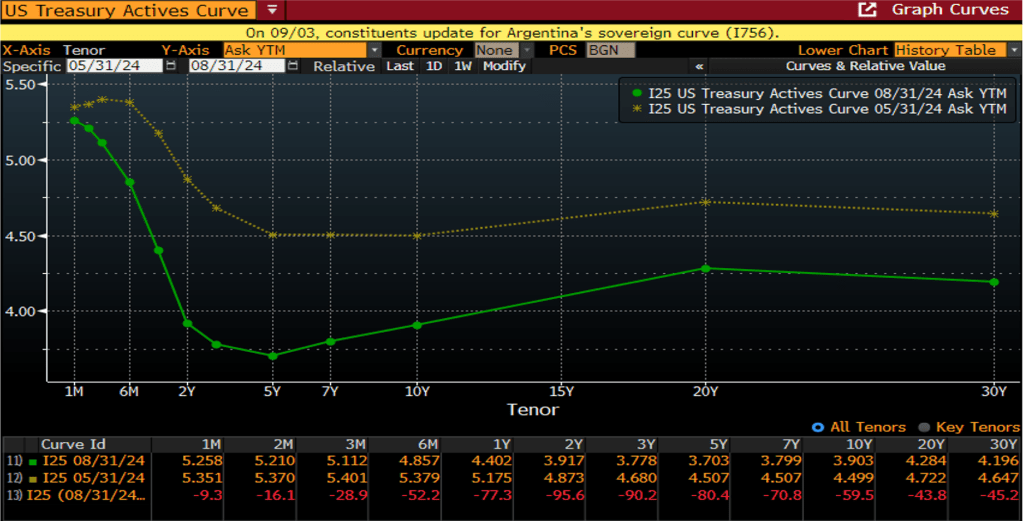

However, as the chart above highlights, rates have moved rather dramatically already without any action by the Fed. Since May 31, 2024, US Treasury yields for both 2-year and 3-year maturities have fallen by >0.9%. By almost any measure, US rates were not high based on long-term averages. Sure, relative to the historically low rates during Covid, US interest rates appeared inflated, but as I’ve pointed out in previous posts, in the decade of the 1990s, the average 10-year Treasury note yield was 6.52% ranging from a peak of 8.06% at the end of 1990 to a low of 4.65% in 1998. I mention the 1990s because it also produced one of the greatest equity market environments. Given that the current yield for the US 10-year Treasury note is only 3.74%, I’d suggest that the present environment isn’t too constraining. In fact, I’d suggest that the environment is fairly loose.

Could it be that there’s been an overreaction to the potential Fed easing? Might Fed action that results in smaller and fewer cuts lead to yields backing up from these levels? Again, who knows? Since none of us do, why don’t you get out of the guessing game and retain a strategy that doesn’t need rates to move down in order to add value. Bring a significant degree of certainty to the management of pensions where great uncertainty is the present name of the game.